What Trump could learn from Stalin

Project 2025 🤝 Operation Bagration, part one

The outcome in modern war will be attained not through the physical destruction of the opponent but rather through a succession of developing manoeuvres that will aim at inducing him to see his ability to comply further with his operational goals. The effect of this mental state leads to operational shock or system paralysis, and ultimately to the disintegration of his operational system.

Vladimir Triandafillov

Just a few days after I decried the left for comparing Donald Trump to Hitler, I’m going to write about another dictator of the Second World War. But at least this isn’t a comparison; merely a lesson.

Trump 2 is still measured in hours, and has already enacted a huge range of executive actions; I’m not going to go through each one, but these were huge and far-reaching decisions that touched a vast range of policies, agencies and

And these orders were enacted almost immediately, too; after declaring a national emergency at the southern border, Trump also axed the CBP One app (used by the Biden administration to help expedite migrants entry into the US) moments after he was sworn-in, effectively cancelling every outstanding appointment.

Trump has only enacted 26 Executive Orders so far, but the reports are there may be more than 100 planned. Trump 2 is clearly far better prepared for power than Trump 1 was; not only is there immediate action, it is across such a broad range of policies that it’s likely his opponents will simply be overwhelmed by his initial blitz, and be unable to block his actions in the same manner as they did last time.

But it doesn’t end here; as well as enacting executive orders to drive policies over the line and enacting them immediately, Trump has coupled them with orders to prevent them being blocked by hostile actors.

As I have written in a previous article, I studied a lot of military strategy at university because war is cool and I am a man. I thought Trump’s strategy so far - advancing on all fronts, supressing opposition not only at the frontline but throughout the entire depth of the battlefield and delivering decisive strategic blow to the enemy's logistical capabilities, making the defense of their frontline more difficult, untenable, or entirely irrelevant - struck me as very reminiscent of the Soviet concept of deep battle.

Let’s get into the theory.

Alexander Svechin is one of the most important Soviet military theorists, often called the "Soviet Clausewitz" due to his influence and foundational work in military strategy. His seminal book, Strategy (1927), defined strategy as the coordination of military operations, resources, and political-economic preparations to achieve war aims. Svechin emphasized the importance of national readiness, including a defense industrial base and sufficient war stocks.

Svechin introduced the concept of operational art, bridging tactics and strategy. He observed that modern warfare, especially during World War I, required long-term tactical attrition and depth-based operations to achieve strategic goals. He defined an "operation" as a sustained military effort directed at achieving significant changes at the theater level, requiring careful coordination of forces, logistics, and objectives.

Later Soviet theorists like Mikhail Tukhachevsky, Vladimir Triandafillov, and Georgii Isserson built upon Svechin's ideas. They developed the concept of "deep battle," which emphasized simultaneous attacks in tactical and operational depth using combined arms, mechanized units, and massed forces. Deep operations aimed to destroy enemy defenses and disrupt their rear to achieve decisive strategic victories.

While Svechin advocated for defensive efforts as a component of a broader strategy, Tukhachevsky prioritized offensive operations, envisioning the Red Army as the vanguard of communist revolution abroad. He recognized that “the impossibility, on a modern wide front, of destroying the enemy army by one blow forces the achievement of that end by a series of successive operations.” Tukhachevsky argued that these operations must be both mobile and offensive in nature. However, like Svechin, he acknowledged the vital importance of logistics and preparation, noting that the Red Army was significantly underdeveloped in these areas.

Triandafillov did much of the intellectual spade work of deep battle; historian David Glantz noted that Triandafillov believed achieving strategic victory required successive operations over a month, advancing 150-200 kilometers, to systematically annihilate the opposing force. Strategic victory, in his view, meant the complete destruction of the enemy’s system. Additionally, Triandafillov introduced the idea of employing tanks supported by air forces to breach tactical defenses and extend offensives into operational depth to fulfill strategic objectives. He argued that this approach necessitated extensive mechanization and industrialization to produce vast quantities of tanks, artillery, aircraft, and airborne units. To execute such operations, he proposed the creation of shock armies—large formations consisting of four to five rifle corps equipped with abundant organic artillery and support units.

Building on Triandafillov’s ideas, Isserson expanded the concept of shock armies to include even larger formations known as shock groups. He delved into the role of fronts—the Red Army’s equivalent of Western army groups—and their subordinate mobile units, such as mechanized corps and cavalry corps, in capitalizing on openings created by the breakthrough echelon of a shock army. This approach emphasized the coordinated exploitation of initial successes to achieve deeper operational and strategic objectives.

The concept of deep battle did, for a time, become accepted as part of Soviet Army doctrine. But after both Svechin and Tukhachevsky were executed during Stalin’s purge of the Red Army - and Triandafillov’s death in an airplane crash - Soviet military theory shifted back to its’ traditional preference, favoring defensive, positional warfare over more dynamic strategies. This also suited the operational capabilities of the under-mechanised Red Army better.

During border conflicts with Japan and the early stages of WW2, individual Red Army officers, including Marshal Georgy Zhukov, re applied deep battle. After initially struggling against the German offensive in the war's early years, the Red Army gradually reversed its fortunes. With experienced troops and improved logistical support, it began to showcase the effectiveness in practice.

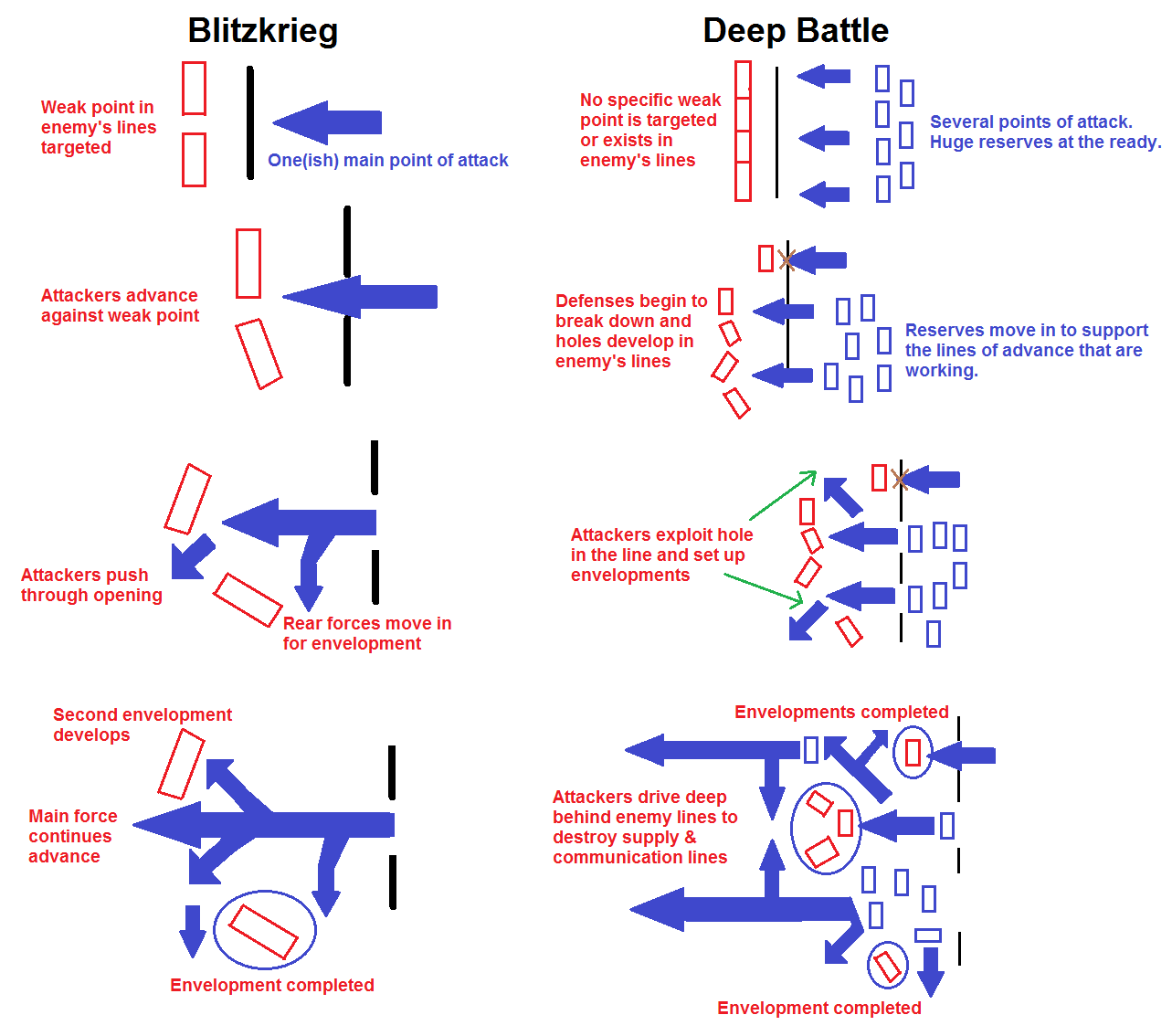

This sounds a bit like Blitzkrieg, but is in fact very different. Blitzkrieg relies on a single blow - the schwerpunkt - to achieve rapid, decisive victories by delivering break throughs at the tactical level, paralyzing the enemy’s ability to resist by isolating enemy defenses and disorganizing their rear. Deep Battle, meanwhile, is designed to achieve a sustained, strategic offensive by defeating the enemy at both tactical and operational depths, using multiple echelons of forces attacking simultaneously across a broad front, with follow-on units exploiting breaches created by the first wave.

>Clausewitz mentioned 🫡