We don’t train, we drain

NHS can't rely on foreign workers forever

This article was first published in UnHerd. Everything I publish elsewhere is shared here for free, as a gift to the nation. But if you want the full picture, become a paid subscriber. It’s just a few quid a month; such is the price genius is reduced to.

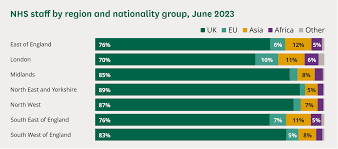

There is a well-worn line that ‘without migration, the NHS would collapse.’ The meme has established itself well within public imagination; polling by Ipsos last year revealed that the public estimate the proportion of NHS workers who are migrants at 42%. In actuality, less than 20% of NHS staff are foreign nationals; but given this does not include migrants who have taken UK Citizenship since arriving, the public may be closer in their estimation than they appear at first glance

The reliance on foreign workers is now at an all-time high; non-UK nationals made up just 13% of the workforce in 2016 and 11.9% in 2009. And despite the NHS Workforce Plan finding this overexposes the ‘to future global shocks and fluctuations in international workforce supply’, the trend is only set to gather pace. Last week, The Telegraph revealed that the Government has frozen funding for nursing degrees. Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson has halted increases to the grants universities receive to offset the higher costs of delivering medical training.

This affects a range of programmes, including nursing, midwifery, and courses for so-called “allied health professionals” such as paramedics, radiographers, and occupational therapists. In a letter to the Office for Students, she confirmed that per-student funding will remain at last year’s level—amounting to a real-terms cut.

This cut will likely result in universities offering a larger proportion of their nursing training places to foreign students in order to offset costs; typical BSc Nursing international fees range from £15,000 to £35,000 per year, while domestic students pay around £9,250

Nursing is therefore set to follow the path as medical placements, which are increasingly squeezing out British students. After the government scrapped the Resident Labour Market Test, medical vacancies no longer had to be advertised to UK citizens first, and employers were no longer required to prove that no suitable UK candidate was available before offering the role to a foreign national.

That has seen a huge increase in the rise of application to specialty training, driven almost entirely by non-UK doctors joining the workforce; in 2024, applications for outstripped the number of posts available by 73%. As a result, stories of final year medical students being left in the dark as to where they will be working have become as regular as the NHS winter crisis stories, with many contemplating finding a new career before they even start.

As the population ages, demand for medical staff will continue to rise. The BMA estimates that the UK will need 11,000 additional medical school places by 2030 to meet future workforce needs. We will naturally need more nurses as well as doctors; but without serious investment in training and education, the NHS’s dependence on foreign-trained staff will only deepen.