Two Nation Tories

Part two of austerity and managerialism

This is part two of a three part series on how some of the mismanagement, missed opportunities and political choices of austerity lead to the managerial politics of today. Links to the other parts are below.

Austerity also ushered in managerialism thanks to its failure to contend with how the engines of growth could sustain the government in the future. Cameron identified that the economic crisis ‘was a monetary crisis, and the most important part of the solution was monetary action: flooding the system with liquidity, preventing the collapse of systemic financial institutions, establishing new sources of finance - government ones, if necessary - to lend money to small businesses now starved of cash.’

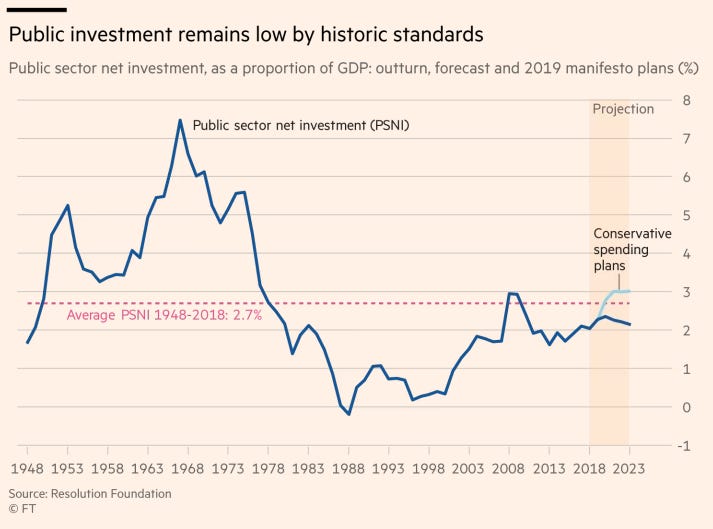

But this increase in liquidity was directed, by and large, through banks and the financial sector. Public investment in infrastructure, meanwhile, was already low by historic UK levels;

And in comparison to other G7 nations;

Austerity saw infrastructure spending cut to help reduce borrowing – despite low interest rates making it an excellent time for the government to borrow.

Cameron was wedded to ‘transformational large scale capital projects’, such as HS2 and Crossrail, whilst prioritising ‘maintenance and smarter use of assets’. That meant a smaller amount of money going on a smaller number of much large, more difficult to complete projects; what this meant in practice was a degradation of the UK’s infrastructure, limiting the potential for growth in the future. Let’s look at energy as an example.

Cameron lauded the launch of Hinckley Point C, the first new British nuclear power station in 20 years; the £20bn project was intended to provide 7% of the UK’s electricity and ‘keep the lights on.’ As an added bonus, then super-into-nuclear Energy Secretary Ed Davey pointed out that ‘57% of the jobs and contracts would go to UK contractors, a way of rebuilding the country's nuclear skills’.

Banking on the huge nuclear project of Hinckley (and Sizewell) C allowed Cameron to pursue the green agenda by forcing the UK off coal far faster than expected; In 2010, the UK used 41.48 million metric tons of coal in energy generation. In 2021, it used just 2.65 million tons – a decrease of more than 95%.

But the reliance on those huge projects to offset the energy lost through producing coal - and the difficulty of delivering them - meant that once they hit inevitable delays, Britain was heading for a crunch in energy generation. Today, we’re facing that energy crunch.

Britain’s total energy supply is falling. Whilst it’s true that energy demand has also fallen, demand hasn’t fallen as fast as supply, so imports of electricity have gone up from 7,144 gigawatt-hours in 2010 to 28,743 gigawatt-hours in 2021. The reality of the over-reliance on these big projects and the failure to deliver them is that Britain is facing an energy price crunch.

Prioritising huge projects over incremental improvements is a common politics; as Bent Flyvbjerg, professor at the Saïd Business School at Oxford University, told the FT;

It’s monument building. Politicians like big projects because they are more spectacular, and they need that to get re-elected. They could spend £1bn on mending potholes, but it would be quickly forgotten.

The commitment to reduce government spending on infrastructure led to a planned relied on large scale private sector investment in these bigger projects - but only £1bn of the promised £20bn was secured. Whilst private investors had ‘enthusiastically put equity into existing infrastructure because there is no risk associated with construction’, they were less keen on the far larger proposed ‘greenfield projects’ beause of the difficultly of delivering them, which include;

Increased cost of providing access to sites

Increased costs of supply to sites

Problems in securing planning, including likely high rate of objections

Environmental issues

The heavy reliance on difficult-to-deliver mega projects meant that, by 2017, greenfield infactructure projects were ‘close to gone.’ Prioritisation of mega projects reduced the money available for smaller, incremental improvements, and Britain’s stagnating growth potential was compounded further by the problems of getting those larger projects off the ground in the first place. Increasing infrastructure investment with rates as low as those available to his government would have been an excellent way to prime Britain for growth. Cameron decided not to take it, primarily because of a fear of hiking interest rates.

In an essay for the New Statesman (no longer available), then Business Secretary Vince Cable argued in favour of taking advantage of record low interest rates to boost infrastructure spending (including on housing). He wrote;

The more controversial question is whether the government should not switch but should borrow more, at current very low interest rates, in order to finance more capital spending: building of schools and colleges; small road and rail projects; more prudential borrowing by councils for house building. This last is crucial to reviving an area which led economic recovery in the 1930s but is now severely depressed... It would target two significant bottlenecks to growth: infrastructure and housing. uch a strategy does not undermine the central objective of reducing the structural deficit, and may assist it by reviving growth … It may complicate the secondary objective of reducing government debt relative to GDP because it entails more state borrowing; but in a weak economy, more public investment increases the numerator and the denominator.

Responding to those calls, Cameron was quick to put his coalition partner in his place;

Those who think we can afford to slow down the rate of fiscal consolidation by borrowing and spending more are jeopardising the nation's finances and they are putting at risk the livelihoods of families up and down the country… They say that by borrowing more they would miraculously end up borrowing less. Let me just say that again: they think borrowing more money would mean borrowing less. Yes, it really is as incredible as that.

And remind him of the task in hand – reducing the nation’s debt;

If we don't deal with it interest rates will rise, homes will be repossessed and businesses will go bust and more and more taxpayer's money will be spent just paying off the interest on our debts. Even just a 1% rise in mortgage interest rates would cost the average family £1,000 in extra debt service payments. So there's not some choice between dealing with our debts and planning for growth.

This final point underlines one of the fundamental choices made during austerity that ensured the advent of today’s managerialism; the distribution of choices along political lines.

Let’s take, for instance, Osbourne’s pivot to a new economic plan in 2012. A contraction at the end of 2011 signalled a looming poor economic outlook for the following year and prompted worries Britain was heading for it’s first double-dip recession since the 1970s. Faced with weak growth, Osbourne moved back his targets to reduce the deficit and - in a move he described as ‘fiscally neutral’ - increased capital spending by £5bn by cutting day-to-day spending by the same amount. But the Eurozone crisis and an unexpected inflation spike meant looking to other, easier way to get the economy going again, as Larry Elliot described;

The government’s original good intentions to rebalance growth towards investment, manufacturing and exports were overtaken by the need to get growth of any sort. If that meant ramping up the property market, so be it.

The process started with the Bank of England’s funding for lending scheme (FLS), under which commercial banks could get access to cheap funds provided they passed them on to small businesses and those seeking mortgages. The money went almost exclusively to the mortgage market. FLS was followed by help to buy, a Treasury plan that offered subsidised mortgages for those people trying to get on the housing ladder.

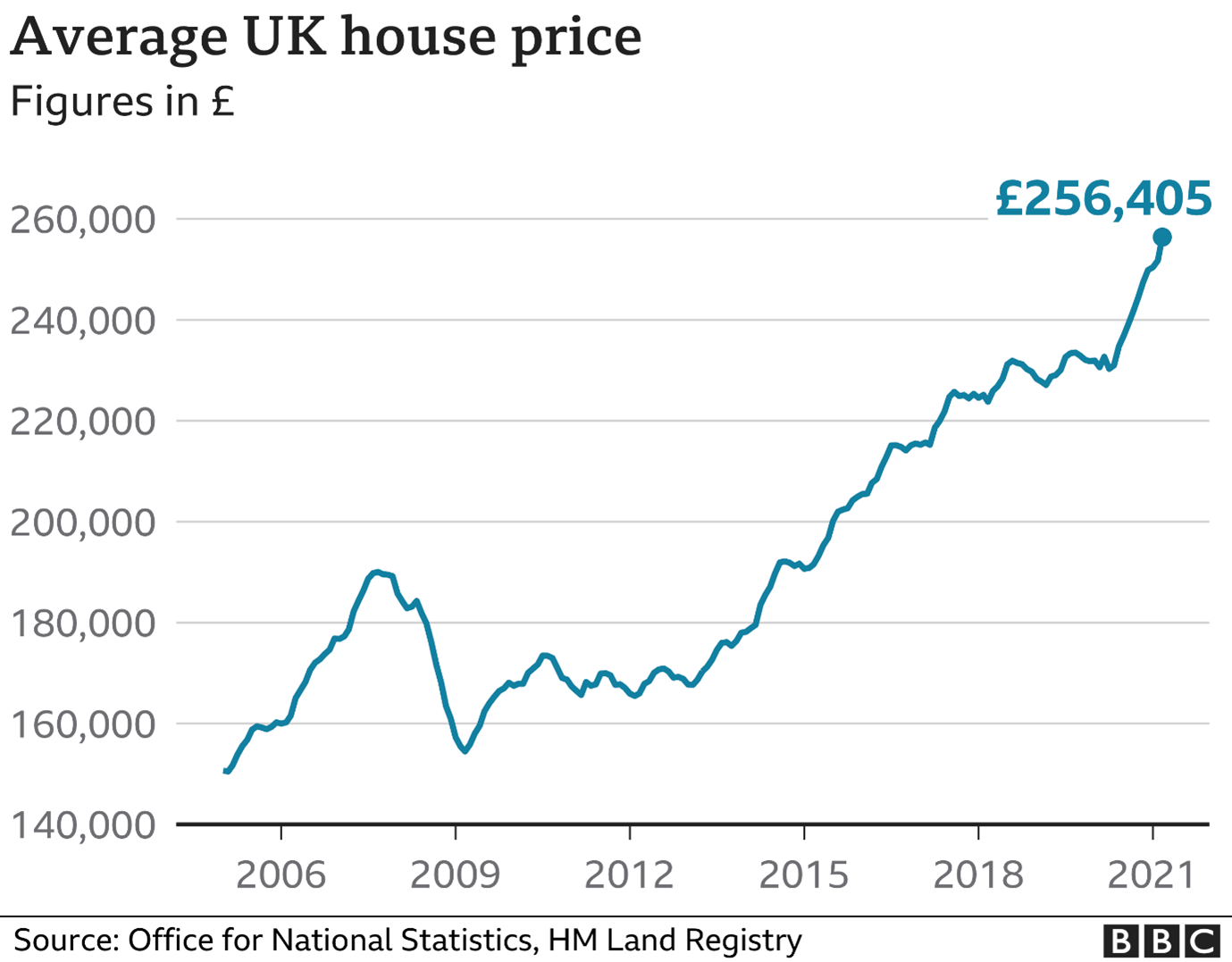

All the while, the Bank of England was sending out the message that there was little or no risk of interest rates going up. Unsurprisingly, the housing market started to motor and, because demand for housing far exceeded supply, property prices started to bubble up.

For the first time since I was born, in 2008 the average house price had actually fallen. Although it wasn’t long before they were rising agin, the (slight) recovery in house prices Osbourne’s Budget prompted was turboboosted by the introuduction of Help To Buy the following year.

By 2013, the economy was back on a move even keel, and with it Osbourne’s standing. But the house price boom again masked an inconvenience; that the years 2010-2015 saw some of the lowest housebuilding rates since World War Two.

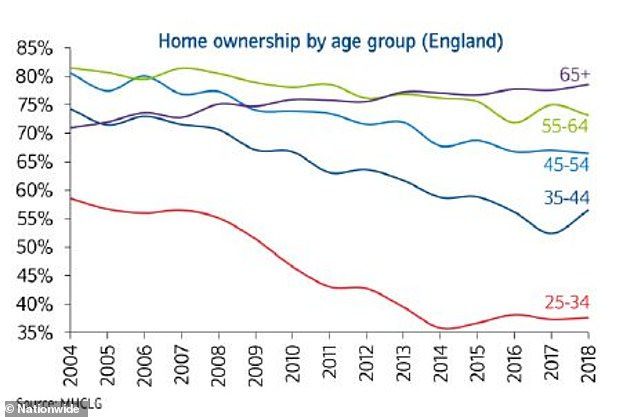

This combination of demand-side reform and constricted supply had the predictable outcome. By the end of this year Help to Buy is set to have cost £29bn, but a recent House of Lords report states that 'evidence suggests that, particularly in areas where help is most needed, these schemes inflate prices by more than their subsidy value’ and recommended that ‘In the long term, funding for home ownership schemes do not provide good value for money, which would be better spent on increasing housing supply. Looking at the rates of homeownership amongst those the scheme was supposedly designed to help, it’s hard to disagree.

Osbourne’s choices drove an increase in house prices but not ownership, repackaging Anthony Eden’s maxim that ‘the ownership of property is not a crime or a sin, but a reward, a right and a responsibility that must be shared’ to a more simplified version: ‘the ownership of property is not a crime or a sin, but must be rewarded.’

Since 2010, the Conservatives have been the party of homeowners, not home ownership. The effect of pursuing a short-to-medium term economic and political rally by both restricting supply and increasing demand for homes had long term effects, however. On top of the cost of delivering the Help to Buy Scheme, Government now spends £23.4bn a year on housing benefit. That’s more than the MoJ, DfT or the Home Office – simply to enable people to live in a housing market that doesn’t function properly.

But the uneven distribution of the choices around housing pales in comparison with the most overtly political choice of the entire austerity era which - to my mind at least - singularly undid Cameron’s promise that ‘we’re all in this together.’ Describing the build up to the decisions of his first Budget in 2010, Cameron writes with pride of his plans;

That was another area I had said before the election we would protect: pensioner’s benefits, such as free bus passes, TV licences and winter fuel payments. In government I was going to go further, and make sure that pensions or proper increases…I protected pensioner’s benefits and, crucially, put in what we called the triple lock, which made sure that pension would rise each year by the same amount as the retail price index, average earnings or 2.5%, whichever was highest.

Following this, Cameron discusses some of the other political choices of that Budget; freezing public sector pay for two years, for instance. On the next page he talks about the emergency budget, which cut £11bn from the welfare budget by:

A combination of measures; housing benefit capped at 400 pounds a week; child benefit frozen for three years; text credits decreased for those earning over 40,000 pounds, but increased for the lowest paid. And benefits would now rise in line with the less generous consumer price index rate of inflation, rather than the retail price index.

Cameron, according to his biography, had to regularly fight both the DWP and Nick Clegg in order to maintain pension levels, and mentions his commitment to the ending of means testing pensioner benefits. Britain’s burden, clearly, was not going to be shouldered equally. As Mike Jones writes;

Mr Cameron’s relationship with the over-60s was not one of support combined with discipline, but rather one of patronage. To secure Tory-friendly seats in an ageing society, Cameron committed his government to protecting pensioners’ winter fuel allowances, free TV licences, free bus passes and triple-locked pensions.

The costs of Cameron’s political choices are clear. The state pension is the largest single item of welfare spending, forecast to make up 42 per cent of the total in 2022-23, and the Department for Work and Pensions puts the total cost for the state pension in 2021-22 at £104.86 billion - an increase from £69.83 billion in 2010 (the year the triple lock was introduced). That guarantee now costs more than most government departments:

Cutting the bloated amount of welfare spending that had developed under New Labour was key to delivering on the austerity agenda. as Cameron puts it:

Without the DWP - which was responsible for a quarter of all government spending - making its fair share of cuts, other departments would face 33% reductions in their budgets, compared to the eventual 19%.

Tackling the huge cost of the triple lock pension now presents an equally important mission. The triple lock is a burden that weighs heaviest on young workers and families, who already face a whole host of problems; real incomes are dropping, buying a home is increasingly unachievable, inflation is high, taxes are even higher and the coming recession is likely to be deep. Their taxes have not just insulated pensioners from the economic realities of the two crises of austerity and Covid, but have gone to making them measurably richer – which cannot be said for claimants of other benefits, as cuts have made our social safety net ‘significantly weaker.’ In fact, older generations have mortgaged the welfare state to the hilt, as Duncan Robinson notes in The Economist;

On average someone born in 1956 will pay about £940,000 in tax throughout their life. But they are forecast to receive state benefits amounting to about £1.2m, or £291,000 net. Someone born in 1996 will enjoy less than half of that figure: a fresh-faced 27-year-old today will receive barely more than someone born in 1931, about a decade before the term ‘welfare state’ was first popularised.

The Triple Lock, far beyond simply entrenching intergenerational inequality, it is now more comparable to a direct transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich; one in four pensioners is a millionaire, whilst the median pensioner, as John Oxley writes, ‘already has more disposable income than the median worker, and is likely to have greater wealth.’

Portioning out such untold riches to the electorate of today by burdening the taxpayer of tomorrow doesn’t just entrench intergenerational disparity; it severely limits the constraints of future political choices. Without the overbearing cost of maintaining the triple lock, for instance, the Government would have significantly more fiscal headroom to respond to public sector pay, which is now significantly below where it was in 2010.

"Even just a 1% rise in mortgage interest rates would cost the average family £1,000 in extra debt service payments." Just imagine!