The perils of polling

Right vs left wing politics belongs in the 20th century

In a recent article for The New Statesman, Senior Data Journalist Ben Walker asked; ‘Labour is seen as much more left wing than Keir Starmer. Does this matter?’

It’s an interesting article looking at the interplay between perceptions of parties and their leaders, but I think even examining this data raises questions about how useful it is in the first place.

Ben starts by looking at how YouGov reports ‘the average Briton’ perceived themselves and party leaders on a right vs left wing scale.

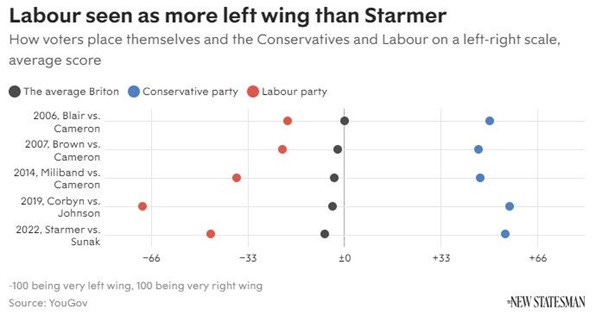

Then compares it to perceptions of the parties:

As you can see from the above graphs, YouGov reckons ‘the average Briton’ is shifting to the left; but every election since that polling began has returned a Conservative Government (albeit not always with an overall majority).

Particularly striking are the 2014 & 2019 results*. Both Miliband & Miliband’s Labour was polled as closer to ‘the average Briton’, yet lost significant ground to Cameron & Cameron’s Conservatives in the 2015 election, a year later. Boris Johnson & Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, meanwhile, were seen as pretty far away from the average voter (yet not as extreme as Corbyn & Corbyn’s Labour Party), but I don’t see the small % difference being enough to deliver an 80-seat majority - especially when compared to the perceptions in 2014 and the results of the 2015 GE.

In the final paragraph, Ben asks; ‘Does this matter? I don’t know.’ I’d argue it does; I think it shows that right vs left wing polling statistics like this are almost totally useless.

YouGov is clearly aware of this. Matthew Smith, Head of Data Journalism, wrote in a blog post (in 2019!) that:

Framing politics in terms of left-wing and right-wing might be simple for politicians, and comforting to activists, but it seems that these terms just aren’t that useful for talking about - or indeed to - the general public… For those who spend their days immersed in Westminster goings on, awareness of how the left-to-right spectrum works is taken for granted. But our results show that the wider public is in fact largely unfamiliar with the categorisation.

This is the wrong way round. As I’ve argued before values-based polling (which looks at what voters think on specific issues) like Onward’s After the Fall, shows a more complex picture that any future Conservative government – or, indeed, the current one - is going to have to grasp if it wants to avoid electoral oblivion:

It offers an insight into the fundamental political shift of the last decade. Politics based on an economic left/right axis belong in the 20th century.

It isn’t that people don’t understand the right vs left wing spectrum. It’s that Westminster is yet to catch up to the fact that it’s no longer suited to representing British political opinion.

Looking at Policy Exchange’s report The People’s Priorities reinforces this view. I’m going to quote at length from the conclusion:

The public overwhelmingly believe that tackling the cost of living (48%) and reducing NHS waiting lists (48%) must be the Government’s priorities for 2023 – a belief that cuts across all age groups, social classes and political affiliations.

Cost of living was the single most common word or phrase entered when people were asked what the biggest problem in the UK was, and was cited by almost half of respondents as a top priority. Improving the NHS, meanwhile, was cited as the top thing the Government should do in order to win the next election.

Meanwhile, the highest priority for those who voted for the Conservative Party in 2019, at 53%, is reducing immigration by stopping the small boats crossing the Channel. Overall, this is considered a priority by over a quarter of all respondents – though is actively opposed by a third of Labour voters.

The ongoing energy crisis is reflected in strong public support for building more self-sufficient energy infrastructure, such as wind, solar and nuclear, while making it easier for first time buyers to afford a house enjoys modest support (20%) amongst the under 25s. To ease the public finances, Three issues stand out as candidates for savings, each of which enjoy strong support from members of the public: cancelling High Speed 2, reducing spending on international aid and reduce public spending on equality and diversity initiatives.

The top self-reported issues from this report are, in order:

Bring down inflation to stop the price of household goods.

Reduce NHS Waiting Lists

Build more self-sufficient energy infrastructure, such as wind, solar and nuclear

Reduce immigration by stopping the small boats crossing the Channel

Reduce people’s taxes to help with the cost of living

But compare this agenda to the earlier right-wing/left-wing polling. YouGov’s ‘average Briton’ is apparently getting more and more left wing; but the most important issues they report to PX is hardly a left-wing agenda. Reducing taxes, lowering immigration, increased energy independence and getting the NHS back on the rails (again) is hardly a radical left-wing agenda.

There’s little surprise that these are the most pressing issues, given their high salience to most people and media focus. Helpfully, PX’s report also looks at underlying support for longer term issues:

One indication of the residual importance of these issue can be seen from Question 6 in our poll, which asked where the Government should be willing to make savings.

So where people indicate they want government to make savings can tell us a lot about what they value, and the PX report shows there are three clear ways people want to make savings:

Reduce public spending on international aid (46%)

Cancel the High Speed 2 rail project (46%)

Reduce public spending on equality and diversity initiatives in the public sector (31%)

Once again ‘the average Briton’, supposedly turning inexorably to the left, favours a strikingly right-wing agenda of cuts - if international aid and equality and diversity aren’t ‘right on culture’ I don’t know what is.

The right vs left wing spectrum isn’t fit to discuss these intricacies, not because it’s too simplistic, but because ‘fundamental political shift of the last decade’ I referenced earlier has rendered it outdated. Right vs left wing positions have been superseded, with more nationalist, social conservatives on one side and more cosmopolitan, social progressives on the other – the lines along which David Goodhart drew his ‘Somewheres vs Anywheres.’

Most people belong to the former group and they also make up an overwhelming portion of the electorate that delivered Boris Johnson his 80-seat majority. They are, as Adrian Pabst describes, ‘broadly communitarian: somehow small-c conservative in their approach to matters of state, law and order, and small-s socialist on public services, fair play and hard work.’ I’d argue against the use of the word ‘socialist’, but that is the general gist

Former Stanford and UCLA professor Guido Tabellini wrote a short briefing on this new realignment. He noted two more changes to go along with the waning of the traditional left/right conflict; first, that support for traditional parties based on the old model of politics shrinks whilst new parties positioned on the new axis surge and second, that many of these new parties run on anti-establishment and anti-elite platforms, campaigning as the ‘true voice of the people’.

Britain, in the finest tradition of British exceptionalism, is not quite true to these trends. The underlying change in political alignment is happening, and there have been rises in anti-establishment and anti-elite platforms, but it has been given a different voice than new parties. There are several reasons for this. The first is that the domination of the electoral system by either Labour or the Conservatives and the FPTP electoral system makes it incredible difficult for new parties to win seats (although Nigel Farage vehicles have achieved admirable effects). The second is that the electorate have been presented with alternate outlets; first the Brexit referendum, then the populist figure of Boris Johnson.

The first-time Tories of 2019 had a long path from Labour. New Labour’s focus on attracting the new, middle-class centrist element of their coalition opened a crevice between them and the party. These older, white, culturally conservative Labour voters in the North provided much of UKIP’s growing support from the mid-2000s, as documented in Matthew Goodwin and Robert Ford’s Revolt on the Right. Their transition through voting UKIP and for Leave before voting Conservative is well documented.

The door to this electorate is still not shut to the Conservatives. As Matthew Goodwin, the PX report’s author, writes on his Substack;

This week, in my polling, only one in ten people who voted Conservative in 2019 have decamped to Labour, which is the same share who have jumped to the radical right Reform but significantly lower than the nearly one in three who say they do not know who to vote for, or prefer not to say.

The slow pick up in Labour support in Onward’s research shows their ties to Labour have not yet been reforged too. So, unless the Conservative colossus stirs once again, there are a huge base of voters after a party to give them a reason to vote.

And there is not much competition from alternative parties. Farage may return, but his economic agenda is aligned to Trussonomics and now majorly out of the step with the electorate. Under Richard Tice Reform suffers from the same problem, and that it talks too much about ‘woke’ issues at the fringe of public interest - rather than putting its most popular policies at the centre of its offering. It is, as John Oxley puts it, "A populist party that doesn't know what's popular".

Meanwhile Laurence Fox vehicle The Reclaim Party is barely passably sensible at best. The SDP also exist, but voters know syncretism when they see it. Simply looting both sides of the aisles in the marketplace of ideas does not make for a coherent platform. The SDP has so far failed to put a fully coherent vision for Britain together, which is why is has actually lost ground in the last 20 years – although it appears to be making something of a turnaround under William Clouston.

The importance of winning this electorate can’t be overstated. Goodwin, again:

There is simply no path back to power for Sunak that does not run through winning back these apathetic, pro-Brexit Tories, whose absence helps to explain why the party’s share of the vote has now fallen off a cliff.

Part of Boris Johnson’s success was appealing to these voters by latching ‘onto a winning formula that worked as well in Stratford as it did in Stockton: a shift to the right on crime, immigration and culture mirrored by a move to the left on economics.’ But, as Adrian Pabst argues, ‘from the outset, the Johnson government struggled to define a coherent position.’

In order to find that coherent position, the Conservatives are going to have to do two things. The first is to drop their notion that politics plays out on a right vs left wing spectrum; as the contrast between right vs left wing polling and values polling shows, it doesn’t offer a useful insight into the British electorate anymore. In fact, it could be actively harmful.

The second is to tie the threads of voter concerns into a coherent and positive ‘politics of Somewhere.’ How far is a 'Somewhere' defined by the core voter issues like the NHS, inflation, reducing immigration, energy dependence etc? What is the story that links their values? Cherry picking economic issues to be vaguely left on and social issues to be vaguely right on is ideologically incoherent. That’s a dangerous game to play in politics, as it makes it more difficult to develop a narrative and people thrive on metaphor, narrative and emotion. As Robert Cialdini writes, ’people don’t counter-argue stories... if you want to be successful in a post-fact world, you do it by presenting accounts, narratives, stories and images and metaphors.’ A good story must be told – when the average person spends so little time thinking about politics, stories are a convenient way of transferring complex concepts into a simply understood, concise narrative.

As I wrote earlier this month, ’What is needed is a future conservativism that appeals to those voters, who broadly match up to David Goodhart’s ‘Somewheres.’ Developing that politics can’t be done using a right vs left wing understanding of politics. It needs more complexity, underpinned by an understanding of the new battlefield of British politics. Only then will conservatives be able to tell a story of how Britain got to where it is and where it’s heading.

*I am disregarding the 2007 result because, even though it shows the same effect, in between that polling and the election was the financial crash.