The Dinner Party Problem

Part two; centrist conformity

The PPE state is shaped by a political class that believes framing is equivalent to fixing; but the homogeneity is not only one of skillset, but worldview. I refer to my CapX piece on Weber, again;

Sadly, it is not a new development to us. Across most modern industrialised democracies, there has been convergence towards professional or middle class overrepresentation in politics. This began with a shift away from rural and agrarian elites, but a second strengthening has now occurred with the marginalisation of working class representation; in 1945, about a quarter of MPs came from a working-class background, based on their pre-parliament occupations. By 2019, this figure had dropped to just 7%.

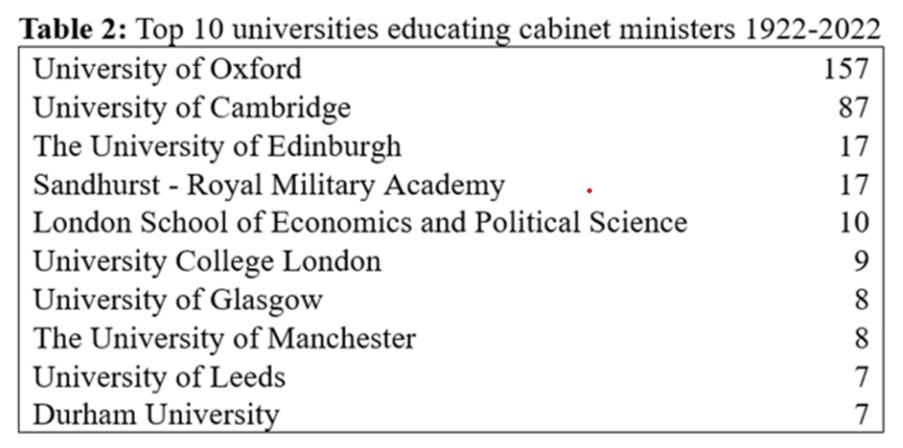

Nor is the social class the only shallow pool from which political talent is drawn; recent research from LSE has shown that over the century from 1922 to 2022, Oxford educated 33% and Cambridge 18% of all British cabinet ministers, meaning over half of all cabinet ministers came from Oxbridge. The rest were drawn from a thin smattering of the better Russel Group unis;

Research into small groups with high levels of cohesiveness and conformity – as would be the case for an elite with such a narrow range of formative experiences, and can be evidenced by the relative political & ideological homogeneity of modern politics - often produce decisions that fail to account for the full breadth of information, or properly consider alternative decisions. This isn’t a particular post-Blair problem; when considering the ill-judged decisions made by the British cabinet during the Suez crisis in 1956, Hugh Thomas and Bertjan Verbeek suggested that the homogeneity of the group in terms of background mean the Cabinet suffered a ‘collective abberation’ of decision making;

The British Cabinet which took the decision to prepare this plan had now been led by Eden for fifteen months. It was a more orthodox Government than any of Churchill’s. Apart from Walter Monckton, an eminent lawyer, none of the Cabinet had much position outside politics. Tough old outsiders like Lords Woolton, Waverley, Chandos, or Cherwell played no part in Eden’s Cabinets, unlike Churchill’s. Including Eden himself, eleven out of the eighteen Cabinet Ministers had been in the House of Commons before 1939, nine were Etonians, six (Eden, Macmillan, Gwilym Lloyd George, Monckton, Salisbury, James Stuart) had served in the First World War (three were MCs, including Eden); another four had fought in the Second World War.19 All save two had been at Oxford or Cambridge. Four had been opponents of appeasement before the Second World War (Eden, Salisbury, Macmillan, Sandys), and five (Butler, Lennox-Boyd, Kilmuir, James Stuart and Home) supporters of it. The youngest Minister was Macleod (forty-three), the eldest Monckton (sixty-two); four Ministers (Monckton, Salisbury, Major Lloyd George and Macmillan) were over sixty.

Verbeek’s work tries to find cognitive explanations to explain why the Cabinet decided to resort to force despite the unlikelihood that US support, deemed essential, would be forthcoming. First of all, Verbeek examines Eden himself;

An analysis of public and private statements by Anthony Eden between 1924 and 195522 shows that his cognitive belief system was guided by the idea, or master belief, that, although conflict is a frequent feature of world politics, in the end, any conflict can be accommodated as long as the parties involved are willing to recognize and respect their mutual security interests. A necessary precondition for conflict resolution, however, is the obeyance of certain standards of international conduct. Essentially, international relations should and can be an area of gentlemanly conduct. This belief structured many other of Eden’s beliefs, including his view of the opponent: it remains possible to accommodate international conflict as long as states and their leaders adhere to certain conventions of correct international behaviour.

Eden’s inner circle – himself, Macmillan, Salisbury and Lloyd – employed collective rationalizations around the timing of the US Prediential elections and highly selective interpretation of messages from Dulles and Eisenhower to convince themselves that US support would be forthcoming after all, despite signs to the contrary. That is because, Verbeek argues, all shared collective assumptions about the US based on the fact they;

shared the same image of the nature of Anglo-US relations: first, they recognized that the United States was the world’s first power, but remained nevertheless convinced that Great Britain was its junior partner with global responsibilities of its own. Second, they were convinced that they had an explicit understanding with the USA that the Middle East was an area which was primarily Great Britain’s sphere of influence. Third, this implied that the USA would not resist the defence by Great Britain of what she perceived to be her legitimate interests

As well as collective blind spots, there is also the issue that a political elite that is so narrow will be unrepresentative of the general population. It is not an issue that politicians are unrepresentative of the people per se, but successful government is made far more difficult if the governing elite is unfamiliar with the lived experiences of the governed.

Politicians now almost exclusively rely on polling data and focus groups to keep them in touch with the electorate. It was unkindly once said to me of David Cameron that he ‘wouldn’t fart without consulting a focus group first.’’ In the past, this effect was mitigated by mass participation in party membership.

Membership of political parties peaked in the 1950s, when the Conservative Party boasted approximately 2.8 million members and Labour 1m; this doesn’t include, of course, an incalculable number of adjacent members; people who might have gone to dinner dances the Tories hosted in hopes of meeting partners, or workers who were members of a union and so felt joining Labour unnecessary. Voting patterns indicate their reach across the electorate was immense. In the ’50s, the main two parties regularly captured around 90% of the vote - sometimes even higher.

This was the result of decades of work in building up reach into society via social organisations such as social clubs and reading groups. But through the later stages of the 20th Century, political parties saw a dramatic fall in membership – not just in Britain, but across developed western nations. Party membership in the UK has declined from roughly 12% of the electorate to under 2% today.

Modern political parties are integral to British democracy; they have a constitutional function to articulating and aggregating the interests of the body politic into a coherent political philosophy and practicable public policy, recruiting and promoting political leaders in the process. But, as Peter Mair argued in Hollowing the Void, the decline of participation in political parties has severed the necessary connection between ruled and rulers; as the range of political backgrounds narrows, our politicians are isolated from broader public sentiment and further embedded in an unreflective peer group with shared assumptions and rationalizations. As in the case of Eden and Suez, this results in cognitive biases that constrains the decision space through collective blind spots.

The increasing homogeneity of both the skillset and background from which politicians are drawn also matters in particular for right wing governance.

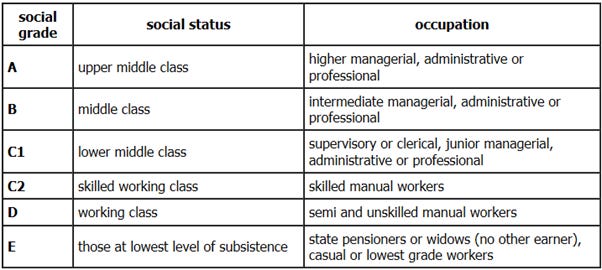

The Conservatives are notably sketchy about their membership numbers, but trends can be drawn. By 2005, total party membership of the Conservatives had plummeted by over 65% from its peak, representing just 1.3% of the electorate. At the last leadership election, 95,194 ballots were cast, a turnout of 72.8% - meaning there were 130,760 members. This decline has left Conservatives reliant on an unrepresentative sample of the electorate, with membership predominantly composed of individuals from the ABC1 socioeconomic category.

As Frances Lasok writes, reversing the trend of mass participation in politics will be difficult (if not impossible), and attempts to democratise political parties in the hopes of encouraging a resurgence in membership may in fact be exacerbating the problem, given how narrow the segments of society they now draw their membership from are;

a mass membership structure without a mass membership is the least democratic option of all: it becomes an oligarchy of age or connections. It causes the limited talent pool in all parties, and the instances at Conservative Parliamentary selections where future Members of Parliament were chosen by four or five people.

Meanwhile, the combination of democratisation of Conservative selections, which now gives party members a direct say, and the narrowing of political participation has seen a narrowed membership select a narrowed elite formation.

One of the most persistent - and concerning - issues of the past 14 years of Conservative government was the presence of - and influence wielded by - individuals who were, in truth, not really right wing.

The type is well known; Woolaston, Grieve, Stewart, Soubry, Grieve, Warsi. On key issues - in particular Brexit, immigration, the constant tightening of the liberal ratchet - they consistently aligned with progressive consensus - which is, per David Goodhart’s Somewheres vs Anywheres, Rob Henderson’s work on the ‘Lanyard Class and Matt Goodwin’s on the ‘New Elite’, most prevalent amongst ABC1s, rather than Conservative voters (or public opinion). I have previously called this type ‘The Eternal Centrist’;

It is notable that Eternal Centrists never offer solid policies or positions to “return” to, but abstract values like moderation or realism. That is because theirs is a politics that offers little but a return to mindless managerialism, the slow grinding of politics as process, rather than principle. What values they do hold are generally economically and socially liberal, and largely indistinguishable from those offered by the parties of the left. That is why so many have so warmly welcomed Starmer into government; he will implement few policies they won’t agree with, with his governing strategy of co-opting “experts” offering a thin cloak against allegations of ideology appealing to their desire for “grown-up” politics. Which is to say, their desire to see meaningful political disagreement, founded on ideological differences, eliminated.

The problem with Eternal Centrists is that they are not meaningfully conservative. As we shall see under the reign of Starmer there will be few social or economic policies that they don’t agree with Labour on, as they have no real ideological grounding in conservatism. Bella Wallersteiner, by accident, made this split clear when she argued that “the party should return to its centrist roots.” The Conservative Party has no centrist roots; its roots lie in maintaining “a hegemony over the right-wing vote whilst also being able to poach votes from the centre”, not the other way around.

To be generous, it’s possible they retain a few conservative instincts, but these are quickly overawed by their desire for the left’s applause, or overridden by their willingness to hand over democratic accountability to “experts”.

Rory Stewart deserves credit for at least being introspective enough to realise he was never really a Tory (his biography makes it clear he was attracted to the Conservatives because they offered the greatest chance of personal advancement, or ‘opportunity to serve’). There are few such cases amongst the many Tory wets who are really Lib Dems, and who walk amongst us still. Caroline Nokes has historically progressive-left framing on gender and immigration. Despite her reputation as a Tory rising star (remember the sword?) Penny Mordaunt never found a liberal ratchet she didn’t leave a few notches tighter. Even after the wipeout at the last election, which was the consequence of the public finally catching up with the differences between the stated preferences we campaign on (right wing) and the revealed preferences we governed by (centrist liberal) The Guardian reported that Tories inside the Cabinet were arguing:

“that the Tories should just ignore Nigel Farage’s party, and the campaign had been too frightened to tackle Reform’s arguments head-on for fear of offending voters who sympathised with them.”

These are, of course, only the public-facing examples; behind the scenes, the problem runs even deeper. Many backroom operators, those who put their bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels of the party and government machine, were not really conservatives either. The examples of this are innumerable, but the one I would alight on is former No 10 adviser Samuel Kasumu took to the BBC to argue that ‘Robert Jenrick has the potential to be the most divisive person in our political history’ in response to the Shadow Justice Secretary (and Man Who Should Be King) calling for action on rape gangs.

This is a perfect illustration of the modus operandi of these types; use their position in the Conservative Party to counter-signal anyone to their right by denouncing them - no matter how factually correct or popular with the electorate their position is - in order to please liberals who despise Tories, and only tolerate the Eternal Centrists because they are not really right-wing. Calling for justice for rape gang victims doesn’t make you more divisive than Oswald Mosley, it just makes an association with whomever it is making the calls inconvenient in progressive circles. Or perhaps I am wrong and they are simply called by a far more noble philosophy than I am, to denounce the thing they served in a far more important role than I did.

There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!

This is known as the Dinner Party Problem – the phenomenon by which supposedly right-wing people moderate their views to align with the dominant progressive consensus in order to avoid being disinvited to dinner parties.

This is not just the result of the narrowing of political backgrounds. There are multiple causes, some of which are inherent in politics; in his 1990 paper Groupthink in Government. A Study of Small Groups and Policy Failure, Dutch academic Paul ‘t Hart argued that the individual calculations of politicians can also explain groupthink, because politicians often base their decisions on whether supporting a policy will advance their future prospects. If the direction of political travel is perceived to be (as in the last 14 years of Tory government) in a broadly liberal or progressive direction – which is then reinforced by a lack of contact with people with differing views – then this recreates the ‘collective aberration’ in decision making we saw in Eden’s Cabinet.