Migration is uneconomic growth

When something grows it gets bigger

Last week, this clip of the economics editor of the Times Mehreen Khan, sparked much debate. In it she claims the government's goals of economic growth and a reduction in immigration numbers are contradictory, saying;

The economy grows because the population grows; tax revenues grow because more people pay those taxes.

I am not going to rehash the arguments around this. The claim has been thoroughly deboonked; the truth is too evident to be swept under. The argument, however, exposes a problem that is becoming increasingly clear, and that is the continued use of GDP as a figure to guide both policy and public debate.

Writing a review of Diane Coyle’s new book The Measure of Progress for The Critic recently, David Goodhart argued it was no longer fit for purpose:

We continue to prostrate ourselves before this statistical idol from the 1940s, despite the fact that it almost comically fails to capture swathes of the modern economy and makes wild guesses (imputations) about much of the rest.

This not only induces what could be an unnecessary and self-reinforcing sense of economic failure but also incentivises GDP-fixated politicians to pursue policies that appease the idol at the expense of human flourishing. As GDP sends increasingly wonky signals, we are setting ourselves up to fail.

Goodhart goes on to detail many of the problems with the use of GDP, mainly focusing on the fact it is hard to collect, unsuited as a measurement to the way modern globalised economies function and the failure to account for much off-book activity such as productive work done in the family home, which will come to be an ever more distortionary problem as our societies age. The one item that Goodhart does not cover, presumably because it has been discussed elsewhere, is the effect GDP has in leading immigration policy.

Since government spending and borrowing is conventionally benchmarked against GDP, what governments talk about when they talk about economic growth is an increase in GDP. Governments are therefore mostly in the business of increasing GDP, because it means more fiscal headroom. This needn’t, but because British politics is now pork barrel inevitably does, mean more spending). Charlie Munger once said “Never, ever think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives”, and the incentive here is to swell GDP by almost any means because growth is both the measure and the prize.

The impact of the incentive is simple. The easiest way to increase GDP is simply to add people, because more people means more economic activity as a whole - which is exactly what Britain has done for the last quarter-century, as I and David Cowan argued in our paper for the Adam Smith Institute:

High levels of low-wage immigration helps to prop up a low-wage, low-productivity economy that is holding Britain back. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is artificially boosted by an increase in population, whilst the costs of delivering public services are suppressed by the insourcing of workforces from increasingly low-wage economies. But the fiscal impact of migration is estimated to only be between +1% and -1% of GDP, according to the Migration Observatory.

This has been recognised for some time. As far back as 2008, a House of Lords report criticised the government for highlighting immigration’s positive effect on GDP, saying it was an irrelevant and misleading criterion and that in terms of income per head any benefit was modest; in the long run, it concluded, ‘the main economic effect of immigration is to enlarge the economy, with relatively small costs and benefits for the incomes of the resident population.’

Yet, because of the distortive effects of immigration on productivity (which are covered in the paper, so I’m not going to rehash here), I disagree that effects have been small; both productivity and per capita GDP have flatlined for a quarter of a century. Since the GDP line go up strategy has delivered relatively little, people are now grasping that GDP is not only a measure increasingly removed from their everyday lives, but a fig leaf for an underlying decline in their material conditions. As Andrew Neil has argued, stagnant per‑capita GDP carries huge political as well as economic weight;

It explains widespread disillusion with Labour and Tories, a general sense nothing works in Britain, that things are not getting better for most people, Brexit (a protest against status quo) and even the rise of Reform (an anti-Tory/Labour vote).

Much energy was put into comprehensively destroying the paper-thin economic arguments in favour of immigration. The only ones left to argue with are hardliners who will simply never accept the validity of any arguments that immigration is not economic rocket fuel (and can therefore be dismissed as ideologues) or those presenting at best surface-level understanding of the economic effects of migration (such as Khan) whose arguments, whilst categorically true, are a sleight of hand.

How to deal with this economic chicanery? One reply to my tweets on this suggested that ‘We need a new word for non-desirable economic "growth" brought about by inflating the size of the population through mass immigration. It should probably be Economic Bloat, or something like that.’

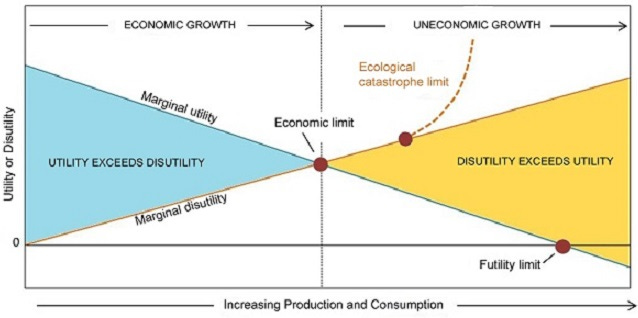

Frankly, I don’t think a new term is necessary. One already exists; Herman Daly, who founded ecological economics, came up with idea of “uneconomic growth” where the benefits of growth (measured as an increase in GDP) are exceeded by the accompanying costs, leading to a net decline in overall quality of life.

I recommend this length obituary in The Conversation if you want to know more about the man, but for the idea read The First Annual Feasta Lecture he gave in 1999, in which he contended that aggregate growth was costing more than it was delivering, and at the margin actually diminishing welfare.

The lecture is mostly centred around the ecological consequences of economic growth (and there is much to disagree with), but it’s clear the principle could be applied to migration. The growth the US was experiencing then is, as now, ‘uneconomic because it's increasing costs faster than its increasing benefits.’ The problem, he argues, is aggregate GDP;

If you want to talk about those things which should grow you have to get away from the aggregate and talk about the parts, you have to get away from macroeconomics back to microeconomics and identify those individual things for which marginal benefits are still greater than marginal costs. That gets you away from this gross policy of just stimulating aggregate economic growth and that's the big problem.

Compare for a moment Khan’s argument with this section of Daly;

The whole idea of micro economics is seeking an optimal level of some activity. As the amount of the activity increases, eventually increasing marginal costs will intersect diminishing marginal benefit. If you grow beyond that it's uneconomic. Optimisation is the essence of micro economics and that implies stopping . So the marginal cost equal marginal revenue rule, which you're all to familiar with if you've had the first course in economics, is aptly called in some textbooks the 'when to stop rule'. I like that term, the 'when to stop' rule.

The is no ‘when to stop’ rule for Khan’s argument. If the economy grows because the population grows and tax revenues grow because more people pay taxes, then permanent economic growth can be obtained by simply increasing the population forever, and an exponential increase in population means an exponential increase in economic growth (and tax revenue). The easiest – the only, given domestic birth rates – way to do that is by supplementing your population with migration. To quote Munger again, show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome; using GDP as a measure means you’re forever to the left of the population Laffer Curve.

The marginal financial benefits we receive from an increase in migration are far exceeded by the marginal costs – and this is only considering its’ impact at the national level. In the same lecture, Daly talks about the potential consequences of eased migration to dissolve national economic boundaries. I quote at length;

Globalisation refers to the economic integration of many formally separate national economies. Globalisation, mainly by free trade and free capital mobility but also to a lesser extent by easing migration, is the effective erasure of national boundaries for economic purposes. What used to be international now becomes inter-regional; what used to be governed by comparative advantage and mutual gain now becomes governed by absolute advantage with no guarantee of mutual gain. What was many becomes one. The very word integration derives from integer of course, integer meaning one, complete or whole. Integration is the act of combining in the one whole. Since there can be only one whole, only one unity with reference to which parts are integrated, it logically follows that global economic integration implies national economic disintegration.

By disintegration I don't mean that productive units disappear, just that they are torn out of the national context and rearranged internationally. As the saying goes, 'to make an omelette, you have to break some eggs'. To integrate the global omelette you have to disintegrate some national eggs. While it sounds nice to say 'world community' we have to face up to its costs at the national level where institutions of community really exist. If you disintegrate real community where it really is at the national level, in the name of a hopeful ideal global attenuated notion of community where it doesn't exist yet, it seems to me very problematic.

By globalising, we take away from nation states their ability to enforce and to enact the polices necessary to internalise external costs, to control population, to do the things that are necessary. We enter into a regime of standards-lowering competition in which trans-national corporations are able to play off one government against another in an attempt to get the lowest possible social and environmental costs internalised into their product and production. The big loser in this process is going to be, as I see it, the labouring class in the countries which in the past, for whatever reason, have managed to maintain high wages, lower population growth, higher standards of environmental internalisation. All of these standards will be competed downward to a world average, which will be, relatively, a low world average. So I see this globalisation as a major obstacle to enacting the kind of radical polices that are necessary in order to avoid this downward spiral of uneconomic growth.

Although I would disagree with the use of the term ‘to a lesser extent’, it must be remembered that this was given in 1999, and that Daly was an unreformed man of the left. But surely his contention that the ‘big loser’ will be the working class in nations that have previously had high wages and low population growth must be born out in any examination of Britain? Two years ago I wrote the following;

Let’s consider the average UK working age person. The Resolution Foundation found recently that after 15 years of wage stagnation, the poor sod was £11,000 worse off than they should be. After that decade and a half of flatlined living standards, their real income is now predicted to drop 5 per cent by the end of 2023.

They face the biggest fall in living standards on record. The OBR predicts they’ll still be 0.4 per cent below pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2028. That will coincide nicely with the highest levels of public spending since the 1970s, funded by the biggest tax burden since World War Two.

That is without factoring the pensions conundrum. The effects of an increasing dependency ratio means that workers’ income tax burden will have to increase by £15bn a year, according to the Resolution Foundation. Pensions will weigh increasingly on a workforce already shrinking — and predicted to shrink even more as the youngest boomers begin to retire. That is in addition to supporting the Triple Lock which, far beyond simply entrenching intergenerational inequality, is now more comparable to a direct transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich.

The fall in living standards does not take into account the single biggest living expense: housing. The average house price is now around nine times the average earnings. The last time it was this high was in 1876. Whilst wages have been flatlining, house prices have risen 20 per cent in the last five years. In 2011, 43 per cent of the 25-to-34 age group were homeowners. Last year it stood at just 24 per cent.

Despite the extraordinary level of tax they are paying to support extraordinary levels of public spending, the average worker will find themselves relatively short of state support. As Duncan Robinson notes in The Economist:

On average someone born in 1956 will pay about £940,000 in tax throughout their life. But they are forecast to receive state benefits amounting to about £1.2m, or £291,000 net. Someone born in 1996 will enjoy less than half of that figure: a fresh-faced 27-year-old today will receive barely more than someone born in 1931, about a decade before the term “welfare state” was first popularised.

I would argue that migration has now far surpassed Daly’s theoretical ‘futility limit’. Evidence clearly shows that GDP per capita and productivity growth have stagnated; the UK’s productivity growth rate averaged 2.1% in the three decades before the financial crisis but then fell to an average 0.6% in 2010 to 2019. This decline has left workers £5,000 a year on average less well off. GDP per capita is also 1.5% less than in 2019 and has grown on average by 0.5% since 2008, whereas it was 2.5% in 1993 to 2008. This means our national income should be 30% higher than current levels.

That is not to mention the effects on house prices - nor on birth rate where, as I have speculated before, there are perfectly reasonable grounds to suspect that immigration is retarding the domestic birth rate. That’s because, whilst immigrants may increase the birth rate – for the first generation at least – the sheer scale of immigration requires massively increases spatial competition for housing. This, naturally, means higher costs, and artificially increased housing costs are causing couples to defer starting families for longer and longer.