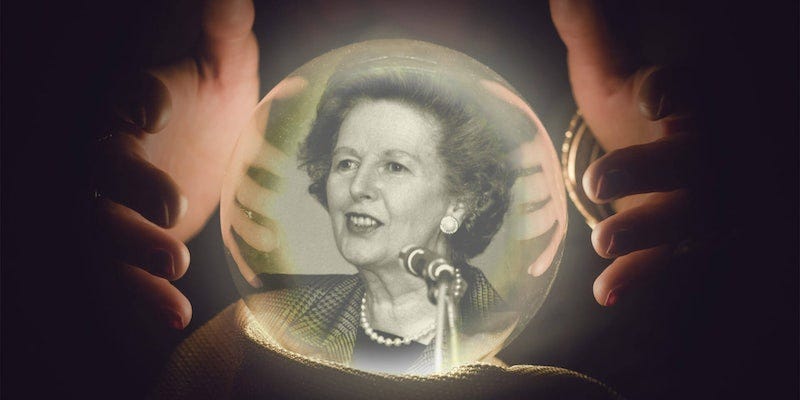

A spectre haunts the Conservatives

Politics started in 1979 and ended in 1990.

In many of Shakespeare’s plays, the ghost of a murdered leader will appear as a portent of imminent doom. Caesar’s appearance to Brutus foreshadows the latter’s death by his own hand at Phillipi; Banquo’s presence at the banquet signals the turning of Macbeth’s fortune; King Hamlet, despite his death, is the driving force behind Hamlet’s descent in madness and eventual death.

Such a spectre appear to both Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss during their contest for Conservative Party leader. Certainly, the party has enough murdered regents to choose from; after all, as David Cameron put it, it is ‘an absolute monarchy interrupted by incredibly violent bouts of regicide’. But it was the ghost of Our Lady of Privatisation that spoke to both candidates in turn, leading both to claim her legacy and to place Her Blessed Memory at the centre of their offerings.

Both Sunak and Truss claimed her legacy instinctively, almost as if they were operating via muscle memory. In the subtly-titled Telegraph article ‘I will be the heir to Margaret Thatcher’, Sunak stated; ‘I am a Thatcherite, I am running as a Thatcherite and I will govern as a Thatcherite.’ He claimed an approach of ‘common sense Thatcherism’, that he would ‘run the economy like Thatcher’. Truss, meanwhile, had long been known to conjure images of the dearly departed in her PR. The campaign saw this aping taken to a new, sartorial, level. When asked the name the party’s greatest leader, both said Thatcher before the air had scarce cleared the throat of the interviewer.

Each claimed different parts of her legacy; Robert Saunders, a historian of modern Britain at the Queen Mary University of London, wrote; “Sunak wants to invoke the early Thatcher, who prioritized taming inflation over quick economic fixes; who raised taxes during a recession and spoke of ‘balancing the books. Truss, by contrast, invokes the triumphant, swashbuckling Thatcher of the later years: a Thatcher who cut taxes, ‘won the Cold War’ and towered over British politics.”

The party’s turn to Thatcher was entirely predictable; she also dealt with inflation and structural economic problems, and her success in doing so has meant she dominates conceptions of right-wing economic governance. But like Shakespeare’s ghosts, her return should serve as a warning; a warning that the Conservatives may have ask questions a little deeper than ‘Is this person Margaret Thatcher?’ should they want to avoid shuffling off their electoral coil.

This was the first meaningful leadership selection in which Europe was not the central issue since David Cameron won the 2005 leadership contest, almost two decades ago. Now that the issue of Europe has now been decisively dispatched with - at least as the defining political issue of the day - the Conservative Party today is not so certain of either itself or its purpose. Throughout the Brexit negotiations membership of the party was divided into two old, but suddenly more distinctly opposed, camps; Eurosceptic and Europhile. That debate was won by the Eurosceptic wing, and the influence of the progressive Cameronites receded as Boris Johnson became leader and the 2019 election seeing an influx of Red Wall MPs, changing the makeup of the party.

But once the final victory of the Eurosceptic camp was secure, it became clear it wasn’t sure what else it believed in. When electing Johnson, the party had again made the decision that winning the next election was more important than ideological factors. What wasn’t accounted for was the fact that the reliance on the electability of Boris Johnson would mean that there were no ideological factors. A victim of its’ own success under the blonde bombshell, the party has sempt incapable of wielding the vast majority it won at the last election because it has been unsure of what its’ driving mission was beyond getting Brexit done.

Faced with economic challenges and a divided, listless party, reaching for Thatcher makes sense; she is a unifying figure, one that all ideological wings of the party respect. Anthony Seldon, historian and biographer of successive British prime ministers, said the tendency to hark back to Thatcher ‘has always been there but is accentuated at the moment because the party doesn’t know what it is or what it wants.’

Her spectral presence is as inescapable as it is insufferable. Facing union trouble? Just do a Thatcher. Declining home ownership rates? A perilous unravelling of a keystone Thatcher policy. What are zoomers crying out for? A zoomer Thatcher. The big problem with Liz Truss? She didn’t learn from Thatcher. The big problem with Rishi Sunak’s New Year speech? He wasn’t Thatcher.

But this cargo-cult worship of Thatcher betrays an intellectual hinterland that seems barren, inert, stagnant. During the election campaign there was no indication of conservative values held beyond the economic; no mention of tradition, stability, security, community or family, no suggestion that society could be made into more than an aggregate of self-seeking individuals. Other than the buzzwords of ‘freedom’ and ‘opportunity’, the campaign singularly failed to outline a grand conservative vision for the future. Thatcher’s use as a leitmotif reduced the Conservative offering to low tax, high growth and precious little else.

Thatcher faced different problems - the excesses of the post-war settlement -– and, more importantly, different opportunities. The scale and range of the electorate that backed the Tories in 2019 showed a path to power the Conservatives should have seized on. Rather than asking ‘what would Margaret Thatcher do’, we should be asking what an ideologically coherent appeal to these voters looks like.

I described the 2019 electorate in detail in The Critic a while back. Broadly speaking;

‘They hold conservative social values when it comes to law and order or matters of state but in economic terms they are both interventionist and redistributive. They are happy with a tax-and-spend agenda, have little appetite for cutting either spending or taxes, and their sense of fairness means they want a government that intervenes to tackle issues like rising inequality and low pay. They don’t see freedom, as Liz Truss did, as the ultimate political virtue. They want an economy that raises the standard of living for everyone and a state that places emphasis on British values, order and stability.’

What is needed is a future conservativism that appeals to those voters, who broadly match up to David Goodhart’s ‘Somewheres.’ But it can’t based on yesterday’s solutions to yesterday’s problems, but today’s answers to today’s problems.

Those problems require a conservativism that recognises that the over-expansion of the welfare state into almost every aspect of citizen’s lives has resulted in a society that has privatised its rights and nationalised its responsibilities. It will need to recognise the terrible outcomes of this overextension in terms of health, social issues, finance and personal responsibility and seek to redress that balance.

It will need to be a conservativism that recognises the need for the state do do a lot less, but perform that significantly more limited role significantly more capably. I would argue very strongly that the 2019 electorate don’t care how much we spend on the Border Force as long as it actually protects our borders - but they do mind how much we spend on the Arts Council, on point of principle that it’s not something government should be funding so generously in the first place.

Economically it will need to take an interest in building up Britain’s resilience, following an active agenda that takes difficult decisions to force necessary infrastructure improvements through. If interventionism is what is required to rebuild our manufacturing base, to reduce our dependence on energy imports and to make sure Britain has a transport infrastructure that can still transport people in 20 years, then an interventionist conservativism it must be.

It will need to recognise that the green agenda can be a spur to growth and an opportunity to bring a proper engineering base back to the UK, but that pursuing it can’t entail a decline in living standards.

This conservativism will recognises the need for the state to rebuild the nation’s social fabric to create stable, cooperative and contented communities - and seizes the opportunity to do that (at the same time drastically reducing it’s role) by building up relationships and institutions that provide a sense of belonging. And this agenda has to result in an increase in personal (and corresponding decrease in government) responsibility by genuine devolution, not by synthetic top-down attempts to induce community via ‘community hubs’ or ‘community workers’.

It will need to redress the intergenerational disparity, giving young people a reason to stay by enabling home ownership and redressing their outsize tax burden - at the expense, if necessary, of more happier generations. On disparity more generally it will have to work to establish a more level playing field, directing its energies at creating an economy that raises the standard of living for everyone, rather than focussing on redistributing the spoils of the victors.

It needs a conservativism that is unashamedly, unabashedly working for the people of Britain, prepared to take a few knocks on the international stage in pursuit of the common good of its’ citizens rather than some nebulous notion of the international ‘common good.’ That might mean being prepared to provide government support to strategically important industries, refusing to surrender every British interests to global ones, or taking hard decisions on the involvement of other states, masquerading as private companied, in the economy.

It will recognise that importing cheap foreign labour is not a sustainable way to un an economy, and recognises that diversity also comes with costs. It will recognise that a border unenforced through weakness is the sign of a failed state, not a testament to toleration.

Finally it will need to recognise that the agenda of unrestricted social liberalism that has been in power for the last 30 years has not come without cost. The almost complete removal of constraints on individual freedom has had a huge impact on social stability, respect for tradition and adherence of British values. It will need to recognise that freedom is not the ultimate political virtue, but must be balanced against values, order and stability.

Boris, through his innate electability, opened the door to a whole new swath of voters. It may be that the door is already shut to them in 2024, but it may be too late to salvage the next election. Once voters have switched once, it is a lot easier for them to switch again.